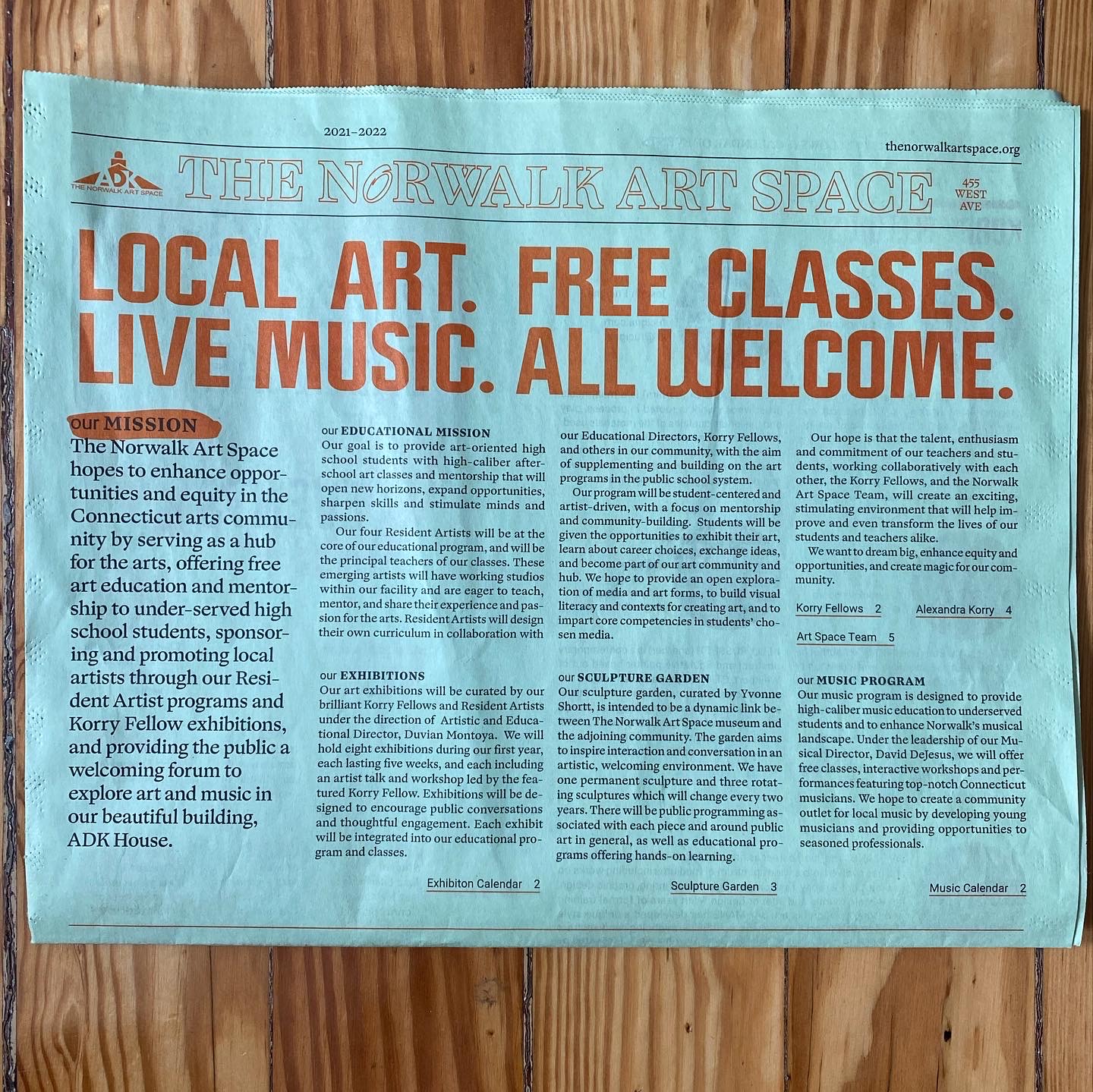

The Norwalk Art Space is a new, non-collecting, contemporary art museum. Its mission is to try to increase opportunities by supporting local and emerging artists, offering free classes and public access to art and culture, and strengthening education equity.

In 1942, an exhibition titled First Papers of Surrealism was mounted in a room in the Whitelaw Reid Mansion (now the orangery at the New York Palace). On the opening night, much to the surprise of the attendees, twelve children burst into the room and began to play–half of them soccer, baseball, and basketball, the other half, jacks and hopscotch. When anyone would ask the children what they were doing, the children responded: doing as Mr. Duchamp told us. And where was this Mr. Duchamp who told the twelve children to go play their outdoor sports inside a New York City mansion exhibiting the masters of surrealist art? Absent.

Marcel Duchamp is known for being the artist who set Western art history on a radical path after buying a urinal from a plumbing supply shop in 1917 and displaying it as an artwork titled, “Fountain.” This act initiated a series of intellectual movements that questioned the presumed sanctity of art. What made an artist an artist? What made an artwork different from a box of Brillo soap pads (Andy Warhol), a Hoover convertible (Jeff Koons), or someone’s messy bed (Tracey Emin)? The twelve playing children during the First Papers of Surrealism were an extension of this theme. What, for example, made the act of drawing as a professional artist different from the drawing one might do in childhood? What about exhibiting works of art in a room of a home transformed that room from a domestic space into a public one?

This paper you are reading is also an exercise in transformations. The corner of West Ave and Butler Street has been, over these last eighteen months, changed. Where once sat a carpet warehouse, and before that the First Church of Christ Scientist, is now The Norwalk Art Space. Young people will make art indoors, music will play outside. A bright orange, sixteen-foot sculpture by Gilbert Boro will permanently mark the spot. Fluorescent orange and green rectangular mounds are new places to sit and wait for the bus. The city of Norwalk offers shopping, bars, restaurants, and now a free art museum and art-themed cafe.

The transformation of West and Butler is one in a series of transformations we’ve all experienced this past year. An international pandemic has impacted each of us individually and catalyzed changes in our culture and society. Our foundational institutions–such as law enforcement, public health, education, and the law–have all come under intense scrutiny. Following the protests of 2020, historian Robin D.G. Kelley has said that the U.S. is experiencing “a third Reconstruction,” referencing the post-Civil War period of the same name. We’ve also come to understand how we relate to one another as a society differently. The emergence of a highly infectious disease has highlighted just how socially interdependent we all are. Indeed, some of the transformations we have experienced lately were uniquely brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. In other cases, the pandemic has only served to accelerate what was otherwise a long-time coming.

Throughout history, art has played a defining role in these kinds of moments. When society has been at a crossroads, confronted with the challenge of leaving behind one way of life for another, art has served as a connective tissue between old and new. This might be because there’s a way that art can register the things that otherwise fall through the gaps of a large-scale transformation: how people were feeling on a particular day, what objects provided comfort, places people wanted to go. The Norwalk Art Space is opening at a time of just such a crossroads.

The Norwalk Art Space is a non-collecting, contemporary art museum dedicated to celebrating local artists and committed to strengthening arts education for the community. Local art has never gotten the second-chance rebranding that eating or shopping locally has in recent years. In an oversaturated and unforgiving art market, the term “local” can be wielded like a weapon, used to diminish someone’s talent and qualify their participation in history. Think about it: if you’re of a certain age and have been living in the tri-state area for long enough, there’s a decent chance you may have seen local New Jersey artist Bruce Springsteen play on the boardwalk “down the Shore.” Or perhaps you’ve seen a movie with local actress, Fairfield-born, Meg Ryan? There’s potentially something slightly ridiculous in the idea of a “local artist,” as perhaps these last two rhetorical questions show. What delimits the definition of “local?” Often for art, “local” is used to indicate where art is made. Yet in a world where we can order food from Kolkata, stream films from Rio de Janeiro, and FaceTime with someone in Minsk, sometimes it seems the only local thing of any certainty is our server space (and even that can be fleeting with the right VPN).

A commitment to the local can be a radical act in a globalized world. Scaling up, to be bigger, to be better, to reach more people: these have all been things presumed to be goals in themselves. Yet the pandemic has forced a break with old paradigms that consider “local” synonymous with “provincial” and “global” with “innovative.” Our time spent restricting our social worlds to the space of our living room drives home the point that large-scale, historical moments begin as local events. History will describe this moment as when the world shut down and the workforce went home. We know it as the time we spent working from our couch; small, cumulative moments adding up to a big one.

This is similarly what is significant about the First Papers of Surrealism. Taking place just one year after the U.S. entered WWII, the exhibition is memorable not for the masters of Surrealism who were on display but instead for the twelve, local children who came bounding into the room with their jacks and basketballs. This moment isn’t memorable to art historians because of the novelty of children playing where they weren’t supposed to, though. It’s because of the way art allowed these local kids to capture a moment in which a global event was experienced locally. The way life in the exhibition room was disrupted and the people inside forced to adapt felt like an outward expression of the anxiety many were feeling internally about entering into another world war. Life in 1942 was proceeding on as normal and yet everything was about to change, in ways that were as-yet still unforeseen. It was stressful, and audiences appreciated the way this encounter with Surrealism allowed them to confront their fears, face-on, in less threatening terms.

As The Norwalk Art Space opens its doors for the first time, it has already begun to bear the marks of a world undergoing tremendous change. A commitment to creating success in, and for, the local community is just one thing that sets The Norwalk Art Space apart. Working to be a museum that is responsive to the ways our society is changing, is another. For example, a recent study found that 85% of artists in museum collections in the U.S. are white and male. Not so for The Norwalk Art Space, whose incoming Resident Artists and Korry Fellows (more about them later) are two-thirds female-identifying, and who more closely reflect Norwalk’s diverse population.

The Norwalk Art Space is opening at a time when social accountability is one of the greatest challenges facing museums today. As institutions, museums need to maintain the trust of the public. However, as guardians of history and culture, museums are not excluded from social and political debates. While the public may look to museums to intervene in these debates, the missions of public-serving institutions don’t always support this. As a result, maintaining openness and tolerance–particularly at a time of polarizing politics–can force hard conversations about the role of the museum in a modern world. While we can’t predict what kind of institution The Norwalk Art Space will ultimately be, the details of the museum’s origins, and its attention to the evolving relationship to what it means to be “local,” seem to signal a museum that is ready for these hard conversations.

A Story in the Details

A defining characteristic of a museum is the way it stores–either temporarily or permanently–objects that, when seen together, help us to understand a bigger issue in more complexity than if we only read about it. For example, in 2018 the Smithsonian received “papers and personal objects” from the family of Matthew Shepard, the 21-year-old openly gay college student who was murdered in Wyoming in 1998. Matthew’s murder caused national outrage and was a partial catalyst for The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2009. Shaping a person’s legacy, especially when their life has been tragically cut short, is a challenging and delicate task. It’s impossible to expect that one narrative can encompass all that one person’s life meant. This is where objects can help, offsetting any single narrative from becoming the dominant one. Among the collection of personal objects the Smithsonian will receive from the Shepard family: a boy’s superman cape, condolence cards to Judy and Dennis Shepard; an activity sheet where a young Matthew misspells “stuped.”

The ADK House (which houses The Norwalk Art Space) might be brand-new but it too has already begun to collect objects of meaning. Enter the brick building and walk downstairs. Pay attention to the globular lighting fixtures, the orange stair rail, the green risers, and the resin-plated wall. These architectural details are the heirlooms of Alexandra Davern Korry, founder of The Norwalk Art Space, who passed away before this project was complete. Memorials and tributes tell us about Alexandra’s life as a pioneering and visionary lawyer and civil rights activist, unwilling to accept the status quo or conventional wisdom, a brilliant maverick who was enduringly compassionate. But the lighting fixtures, the risers, the green Exit wall, the shade of white paint on the walls (scrupulously chosen from a survey of what seemed like 200 options, her husband explains): these tell us a story about Alexandra, too. Not just about a woman with an attention to detail (she was that, also) but also about someone who was committed to building enduring solutions to structural problems.

Education: A Shifting Landscape

As Chair of the New York Advisory Committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Alexandra consistently challenged practices that disadvantaged or unfairly targeted low-income and racial-ethnic minority communities. Education is an area in which society can fail U.S. children, particularly those who are low-income and/or BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color). Education and social mobility–the ability to move up and down a social hierarchy such as class or social status–are often linked, meaning that often the more education you have the better chance you have to make more money and have more social influence. For this reason, The Norwalk Art Space has made free education a cornerstone of its programming.

Art education can increase opportunities for upward social mobility. While art hasn’t always offered a lucrative career path, the narrow focus in recent years on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects is being challenged. In its place educators are calling for STEAM: science technology, engineering, art, and mathematics. In what has been called the “STEAM Revolution,” educators argue that art and other creative subjects outside of the “hard” disciplines are essential for teaching and promoting critical thinking skills in students. The value of such an approach is not lost on the educators at The Norwalk Art Space, whose backgrounds in museum education, art education, and art therapy are all part of traditions that have long championed the value of humanities-based approaches for education.

Each year, the team at The Norwalk Art Space will select eight artists to run their education program. Four of the artists will be Resident Artists. These artists are so named because they will temporarily “reside” at ADK House via a free studio space at the bottom level of the building. Resident Artists will be local artists who are early in their careers and chosen for their promising talent. In exchange for career support and studio space, Resident Artists commit to also teaching courses based on their specialized skill or practice. The other four artists selected annually will be named Korry Fellows (though this year, due to overwhelming enthusiasm, the space is lucky to have five Fellows). Korry Fellows will be mid-career artists selected for their strong portfolios and established careers. Korry Fellows will teach workshops–one-off, intensive teaching sessions–that can either introduce students to a new artistic practice or help to deepen an existing one.

In addition to The Norwalk Art Space classes, the museum has also made an effort to embed itself in the existing education system in Norwalk. The Norwalk Art Space’s Artistic and Educational Director Duvian Montoya has, with the help of Educational Co-Director Darcy Hicks, begun talks with Norwalk public schools about a series of initiatives aimed at inspiring young people to get involved in ar, and encouraging those who already are. (Without revealing too much, let’s just say keep an eye on the bus stop in front of the museum: it’s about to get a lot more colorful.)

These kinds of projects which tie together city, community, and institution are important because they signal how The Norwalk Art Space is thinking about its role in art and the community. By using its influence as an institution and working with existing infrastructures to amplify art education, The Norwalk Art Space shows that it understands success as being tied to that of its youngest thinkers and makers.

Doing Better by Working Together

As society is confronted with the challenge of building a more just world, individual people are also looking to make a difference. Dean Spade, a lawyer, trans-activist, and author Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next), has emphasized the importance of understanding social change as something that should happen at both the level of the institution and the individual. Challenges to legal frameworks and policies are important for building long-term change, but it’s equally important that individuals are mobilized around the issues that affect them most. Doing so empowers people to create opportunities for themselves and can help build supportive networks that are more responsive to day-to-day needs. This two-pronged approach to change and social justice was a principle Alexandra lived out in her daily life. At the same time that Alexandra worked to promote civil rights from legal and policy perspectives, she also committed many hours to teaching and mentorship at the Harlem after-school program she chaired, Columbia Law School, and her law firm.

The Norwalk Art Space is following in Alexandra’s path. Not only does the museum aim to build an infrastructure for creating educational opportunities, but it’s also focused on mobilizing a community of artists that can support each other. This begins with the Resident Artists, each of whom will be encouraged to work with a Korry Fellow on the basis of shared qualities in lived experience, artistic style or medium, or career goals. These introductions form the basis of The Norwalk Art Space’s mentorship program. Through this relationship, Korry Fellows can be available to help Resident Artists with everything from emotional support, to masterclasses in technique, to advice on business basics such as how to price your work, how to approach galleries, and how to write an artist statement. In this way, the mentoring relationship works to pass down insider knowledge and opportunities through generations of artists.

Supporting intergenerational mentoring is another expression of The Norwalk Art Space’s commitment to enhance opportunities for success. Studies have shown that upward social mobility can be affected by causes outside of any one person’s lifetime. For example, data from education equity studies have shown an overlooked influence of multigenerational effects on education and social mobility. These studies support the idea that poverty and affluence are conditions that are inherited, not because of any biological reason (despite the metaphor), but because of the ways institutions–which outlive individuals–enable it. As Ezekiel Dixon-Román explains in his book Inheriting Possibility: Social Reproduction and Quantification in Education, institutions promote inheritance through things like “legal arrangements of generation-skipping trusts, the legacy system of Ivy League schools, wealth accumulation and transfer, and segregation and housing discrimination,” and each of these can be more or less influenced by their specific geographical and historical context. Put another way, opportunity isn’t solely the outcome of merit. It can instead be heavily influenced by where and when you, your parents, and your grandparents were born, and the decisions they made in their lifetimes about their work and education. As an alternative, The Norwalk Art Space’s emphasis on mentoring and education both in and outside of the classroom passes down opportunity through the mobilization of a community.

Our New Local

While it’s common to talk about “the artworld,” this phrase actually has a specific origin and meaning. In 1964 philosopher Arthur Danto wrote an essay of the same title in which he lamented how anything, no matter how quotidian, could be seen as art. He blamed this on the people who made up “the artworld,” or the art professionals associated with certain art institutions who were the sole arbiters of what did, and did not, get to be “art.”

Danto’s theory of “the artworld” put distance between art and “regular” people. The only reason why a Brillo box, a convertible Hoover, or someone’s bed were seen as art was because those few people in “the artworld” said so. If someone in the general public was confused about that, or didn’t “get it,” it was because of their lack of art history knowledge and their place outside “the artworld.”

We’ve come a long way from how Danto viewed the artworld. Museums increasingly see their role as a public good and they work hard to be welcoming to their audiences. Yet somehow Danto’s diagnosis of the gulf between art and audience still has a sad ring of truth to it. What is alienating audiences from enjoying contemporary art? Is it museum entry fees? Is it not having a museum close enough to visit? Or are we put off by the specter of an artworld that doesn’t see us as part of it?

Once upon a time, too, the word “local” was also a way of separating out the “us” from the art world. “Local” was a way to bundle up an artist with their artwork and to place both outside of an art world proper. But times have changed. We have changed. Art has changed. And what’s local has changed, too. After having sheltered in our homes for over a year, the local is what’s kept us alive. Our local takeout place. Our local pharmacy. A local park. The word “local” doesn’t just automatically shapeshift to mean something else because it enters the discourse of art. Local is best when it’s at its simplest: a word used to describe a place and time, an answer to the question, “Where were you when?”

So now, we have a new answer to what’s local: an art museum, The Norwalk Art Space. Not a space limited by the place in which it is located. Not a space qualified by the geographic range of artists and young people it supports. Instead, a space that is local because it is rooted in a community and rooting for the success of that community.

“Local” is a museum that wants to teach you how to be a great artist. “Local” is a museum that’s free because it wants more people to visit (not fewer). “Local” is a museum with an art cafe: once a church altar, now a place for eating food with friends and for displaying works in progress. “Local” is the building block of transformative history: a room in someone’s home became an exhibition space became a space filled with children playing games; a church became a carpet warehouse became a museum and a classroom. The Norwalk Art Space is a space in use, a space for the community populated by the people, history, and material of the community.

“Local” is an invitation to come in.